In a world where global trade is increasingly disrupted by broken supply chains, sanctions, and power politics, India and the European Union have taken a strong and timely step by signing the India–EU Free Trade Agreement. With trade already at $136 billion, Europe accounting for 16% of India’s foreign investment, and the deal expected to generate another $75 billion in exports, the partnership goes beyond economics and strengthens strategic ties. For Europe, the agreement helps reduce dependence on China and the US, while for India, it guarantees better access to the world’s largest single market. Together, India and the EU are presenting themselves as reliable partners and sources of stability in a multipolar world that aims to be governed by clear rules rather than power rivalries.

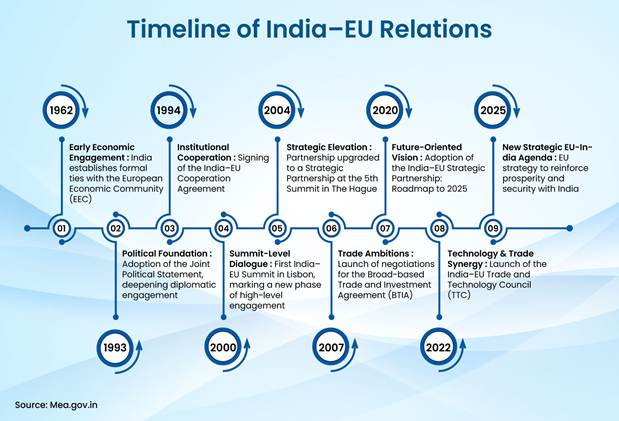

How India-EU Ties have Evolved Over Time?

Phase I: Normative Engagement (1990s–2004)

After the Cold War, India and the European Union reshaped their relationship around trade, development cooperation, and shared democratic values. This gradual engagement culminated in the declaration of a Strategic Partnership in 2004.

Phase II: Institutional Optimism, Limited Convergence (2005–2013)

New frameworks such as the Joint Action Plan (2005) and talks on the Broad-based Trade and Investment Agreement (BTIA) from 2007 expanded formal dialogue. However, momentum slowed due to the Eurozone crisis, regulatory differences, and weak political commitment, exposing a clear gap between big goals and actual outcomes.

Phase III: Strategic Drift amid Global Uncertainty (2014–2019)

Although trade continued to grow, the partnership failed to reach its full potential. Europe became more inward-looking, while India broadened its global engagements. As a result, ties stayed largely economic and transactional, with limited geopolitical depth.

Phase IV: Strategic Recalibration (2020–2024)

The Covid-19 pandemic, supply-chain disruptions, and China’s growing assertiveness pushed both sides closer on issues like resilience, technology, and the Indo-Pacific. This led to the revival of trade negotiations and the launch of the Trade and Technology Council in 2022. The FTA began to be seen not just as a trade deal, but as a strategic tool for diversification, resilience, and autonomy.

Phase V: Strategic Consolidation (2025–present)

The signing of the India–EU FTA, along with cooperation on security, defence, and mobility, marks a shift from limited sector-wise cooperation to deep strategic alignment. India and the EU now see themselves as joint partners in shaping a stable, multipolar, and rules-based global order.

What are the Key Provisions of the INDIA-EU FTA?

- Unprecedented Tariff Liberalisation in Goods Trade

- The agreement gives India almost complete preferential access to the European Union market, covering more than 99% of Indian exports by value. Many labour-intensive sectors will get immediate zero-duty access, while sensitive products will see tariffs reduced or removed gradually over time. For certain sectors such as automobiles, steel, and selected agricultural and marine products, Tariff Rate Quotas (TRQs) have been used to balance better market access with protection of domestic industries.

- Calibrated Reciprocal Market Access for EU Exports

- India has agreed to lower tariffs on 92.1% of tariff lines, covering 97.5% of EU exports. Sensitive industrial products will see tariffs reduced slowly over a period of 5–10 years. In agriculture, India has adopted a controlled approach by allowing limited access through TRQs for only a few fruit categories. This structure allows Indian manufacturers to benefit from advanced European technology and inputs, lowering costs and improving competitiveness without sudden shocks.

- Product-Specific Rules of Origin (PSRs)

- Clear and detailed rules define what qualifies as an Indian or EU product, ensuring that substantial processing takes place within either partner. These rules are aligned with global value chains to prevent misuse or trade diversion. At the same time, flexibility in sourcing non-originating inputs has been built in, which is especially helpful for MSMEs. The introduction of self-certification through a Statement of Origin further reduces paperwork and compliance costs.

- Safeguarded Agricultural Liberalisation

- The EU has agreed to offer favourable access to Indian agricultural and processed food exports where India is globally competitive. This includes products such as tea, coffee, spices, fruits, vegetables, and processed foods. On the other hand, India has taken a cautious stance by excluding sensitive agricultural sectors from EU market access. Dairy, cereals, poultry, soymeal, and certain fruits and vegetables have been kept out to protect food security, farmer incomes, and rural employment.

- Services Trade: High-Value Commitments

- The EU has opened 144 services sub-sectors to Indian service providers, including IT and IT-enabled services, professional services, business services, and education. These commitments are designed to be predictable and non-discriminatory, giving Indian firms regulatory certainty. India, in turn, has opened 102 services sub-sectors to EU providers, encouraging the inflow of high-technology services, investment, and best global practices into the Indian economy.

- Mobility and Movement of Professionals

- A key achievement of the FTA is a clear and predictable framework for professional mobility. The EU has committed to easier entry for intra-corporate transferees and business visitors, along with access for contractual service suppliers in 37 sectors and independent professionals in 17 sectors. Dependents of intra-corporate transferees will also receive entry and work rights, and provisions have been included to support student mobility and post-study work. In EU member states without specific regulations, AYUSH practitioners will be allowed to practise based on qualifications earned in India. The agreement also lays the foundation for dialogue on Social Security Agreements over five years, aiming to reduce double social security contributions and make professional movement smoother.

- Non-Tariff Barriers and Trade Facilitation

- The EU has committed to cutting non-tariff barriers by improving regulatory transparency, simplifying customs procedures, and strengthening sanitary and phytosanitary measures. These steps directly address long-standing compliance problems faced by Indian exporters, especially in agriculture, food, and manufacturing. India has reciprocated by agreeing to deeper cooperation on customs, trade facilitation, SPS, and technical standards.

- CBAM and the Climate–Trade Interface

- The FTA includes forward-looking assurances related to the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. India has received a Most-Favoured-Nation assurance, meaning any flexibility the EU offers to other countries under CBAM will also apply to India. While engaging constructively on climate issues, India has clearly protected its development priorities, emphasising cooperation over coercion so that environmental rules do not become hidden trade barriers.

- Automobile Tariff Note and Concerns

- Under the FTA, tariffs on car imports into India will be reduced gradually from 110% to 10%, within an annual quota of 250,000 vehicles. Electric vehicles are excluded from this tariff relief. This is expected to benefit European automakers, who currently hold less than 4% of India’s car market, and could encourage new investments. At the same time, concerns remain that early tariff cuts may slow the growth of India’s domestic automobile industry and affect local manufacturers and the emerging EV ecosystem before they become globally competitive.

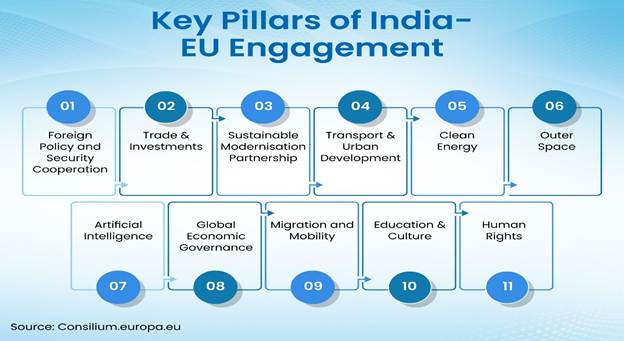

What are the Other Areas of Convergence in India-EU Relations?

- Strategic Autonomy & a Multipolar World Order

- India and the European Union share a common outlook on avoiding rigid bloc politics in an era dominated by US–China rivalry. Both value strategic autonomy, sovereignty, and flexibility, preferring issue-based cooperation rather than binding military or political alliances. This shared approach allows them to act as stabilising middle powers, shaping a multipolar world order instead of aligning with great-power camps. The Joint India–EU Comprehensive Strategic Agenda reaffirmed their shared goals of prosperity and sustainability, while the presence of EU leaders as chief guests at India’s 77th Republic Day symbolised a clear political reset and deeper alignment.

- Defence, Maritime Security & Indo-Pacific Stability

- Security cooperation has grown as both partners face threats such as disrupted sea lanes, cyber risks, and grey-zone coercion in the Indo-Pacific. India contributes its strong regional presence and naval capabilities, while the EU brings expertise in capacity-building and maritime domain awareness. As a result, security has become a key pillar alongside trade and economics. The Security and Defence Partnership expands collaboration in maritime security, cyber defence, counter-terrorism, and joint naval exercises, reflecting a more mature and balanced partnership.

- Supply Chain Resilience & De-Risking from China

- Both India and the EU aim to reduce excessive dependence on concentrated manufacturing hubs, especially China, without resorting to sudden or disruptive decoupling. India offers scale, a large workforce, and manufacturing potential, while the EU provides capital, advanced technology, and high standards. This convergence is driven by practical risk management rather than ideology. EU leaders increasingly see India as a reliable diversification partner, reflected in the fact that EU companies contribute about 16% of India’s total FDI, with over 6,000 European firms operating in the country. Ursula von der Leyen has openly supported this view, stating during the finalisation of a major EU–India trade deal that when India grows, the world becomes more stable, prosperous, and secure.

- Technology Governance & Trusted Digital Ecosystems

- India and the EU also align on how technology should be governed in democratic societies. Unlike the US’s largely market-driven model or China’s state-controlled approach, both favour rules-based digital ecosystems that balance innovation with regulation. Their cooperation covers areas such as artificial intelligence, semiconductors, cyber norms, and digital public infrastructure. The India–EU Trade and Technology Council launched in 2022 has formalised this cooperation, with several working groups now actively coordinating on trusted technologies, resilient supply chains, and green innovation.

- Multilateralism & Global Governance Reform

- At a time when global institutions are under strain from sanctions politics and weakening rules, India and the EU jointly support multilateralism as the foundation of global stability. Both argue that reformed and inclusive multilateral institutions are preferable to unilateral actions. India’s growing global influence and the EU’s normative and regulatory strength increasingly complement each other. This convergence is visible in coordinated positions and cooperation in forums such as the G20, World Trade Organization reform discussions, and international climate negotiations.

What are the Key Areas of Divergence in India-EU Relations?

- “Green Protectionism” and the CBAM Deadlock

- The biggest economic friction between India and the European Union comes from the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). India sees CBAM as a disguised “green tax” that unfairly targets developing economies. From India’s perspective, the mechanism ignores the principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities, placing the same burden on developing industries as on advanced economies. By adding an estimated 20–35% cost to Indian exports, CBAM risks cancelling out many of the tariff benefits promised under the new FTA. Although the FTA includes a Most-Favoured-Nation clause covering CBAM-related flexibilities, it is still unclear how far this will actually protect Indian exporters in practice.

- Geopolitical Dissonance: The Russia–Ukraine Test

- A deep strategic divide remains over the Russia–Ukraine war. The EU expects partners to align with its sanctions regime as part of a values-based foreign policy, while India insists on maintaining strategic autonomy. European leaders argue that India’s purchases of Russian oil indirectly support a war that threatens European security. India, however, views these imports as essential for energy security for its 1.4 billion people, making them non-negotiable. This difference has become a constant diplomatic irritant. In December 2025 alone, India was the third-largest buyer of Russian fossil fuels, importing about €2.3 billion worth, even as the EU pushed for tighter sanctions. India has also abstained on key UN resolutions criticising Russia, diverging from the EU’s unified voting position.

- Digital Sovereignty: GDPR vs. India’s DPDP Act

- Tensions also exist in the digital domain. The EU treats its data protection framework as the global benchmark for “data adequacy,” while India’s Digital Personal Data Protection Act of 2023 gives the government broad powers to access data for national security. This creates a fundamental trust gap. The EU is reluctant to grant India “data secure” or adequacy status, which is critical for high-end IT outsourcing. Concerns centre on the absence of an independent data regulator in India and wide exemptions for state surveillance. As a result, data cooperation remains limited, forcing Indian IT firms to rely on costly Standard Contractual Clauses when serving EU clients, raising compliance costs compared to competitors like Vietnam or the Philippines.

- Mobility Asymmetry: Fortress Europe vs. Talent Export

- Differences are equally sharp on labour mobility. The EU prefers “circular migration,” allowing temporary entry to address workforce shortages caused by ageing populations, while India seeks easier and more permanent access for its IT and healthcare professionals under Mode 4 trade rules. The EU’s approach is driven by security and migration control, including the return of irregular migrants. India, in contrast, sees strict visa rules and non-recognition of Indian qualifications as major trade barriers. Although there is no formal cap on EU Blue Cards, the 2026 mobility arrangement guarantees only 35,000 graduate permits, far below the target of 100,000 multi-year work visas for Indians each year. This limited guarantee creates a bottleneck when compared to India’s vast pool of skilled graduates.

- WTO Subsidy Wars and the Public Stockholding Dispute

- At the World Trade Organization, India and the EU frequently clash over agricultural subsidies. The EU, along with other developed countries, challenges India’s minimum support prices and food grain procurement as trade-distorting subsidies that exceed the 10% limit. India counters that these programmes are essential for food security and farmer livelihoods, especially in a developing economy. At the same time, India points to the EU’s own extensive farm support under so-called non-trade-distorting subsidies. Ahead of the WTO’s 14th Ministerial Conference in March 2026, the EU has proposed changes such as weakening consensus rules, limiting special treatment for developing countries, and delaying the full restoration of the dispute settlement system. These proposals run directly against India’s position, which strongly supports a fair, effective multilateral dispute resolution mechanism to protect developing-country interests.

What Measures are Needed to Enhance India-EU Cooperation?

- Creating a “Green Equivalence” Solution for CBAM

- To ease tensions over the EU’s carbon tax, India and the European Union should work towards a system where their carbon pricing mechanisms are mutually recognised. This would mean technically aligning India’s domestic Carbon Credit Trading Scheme with the EU’s Emissions Trading System. If Indian carbon credits are accepted as equivalent at the source, exporters could pay the carbon cost within India instead of in Europe. This would keep revenues inside India to fund its green transition, while still meeting the EU’s demand for fair competition.

- Using GDPR-Aligned Data Enclaves to Break the Data Deadlock

- Rather than resolving national-level disagreements on data protection all at once, India could carve out specific zones—such as GIFT City—that follow privacy standards equivalent to the EU’s GDPR. These “data enclaves” would operate under stricter, ring-fenced rules, separate from wider national security exemptions. This would allow sensitive, high-value data processing for European clients to continue smoothly, without getting trapped in broader debates around India’s data protection law.

- Shifting Focus to Joint Projects in Third Countries

- To reduce the strain caused by disagreements over Russia, the partnership should focus more on practical cooperation in the Global South. A joint platform for infrastructure projects in Africa and the Indo-Pacific could combine European finance under initiatives like Global Gateway with India’s experience in cost-effective implementation. Working together on projects such as power grids in Kenya or digital payment systems in Vietnam would create shared successes that strengthen trust and insulate the relationship from specific geopolitical disputes.

- Building a Critical Raw Materials Partnership with Value Addition

- Instead of a simple buyer–seller relationship for minerals, India and the EU could form a deeper partnership based on shared processing and value addition. Under such an arrangement, the EU would transfer advanced processing technologies to India in return for secure access to resources like lithium or rare earths. This would help India move up the manufacturing value chain, while giving Europe a diversified and reliable supply that reduces dependence on China.

- Setting Up India–EU Innovation Hubs for Future Technologies

- Finally, both sides should turn their strategic agenda into action by creating joint innovation hubs for critical technologies such as 6G, quantum computing, and advanced semiconductors. These hubs would focus on co-developing technologies rather than simply transferring them. By combining India’s strengths in design, software, and prototyping with Europe’s research infrastructure, the partnership could build a resilient, democratic technology ecosystem that offers a credible alternative to highly concentrated global tech monopolies.

Conclusion

In simple terms, the India–European Union relationship is no longer occasional or limited—it is steadily becoming a deep strategic partnership. Both sides are coming together around shared ideas such as a multipolar world, strategic autonomy, and respect for a rules-based international system.

While the Free Trade Agreement has given this partnership strong momentum, cooperation now goes far beyond trade. It includes security, technology, climate action, and the movement and development of skilled people. Differences will still exist, but handling them through dialogue and mutual understanding rather than pressure or coercion—will be essential. If managed well, India and the EU can together act as reliable pillars of stability in an increasingly divided and uncertain global order.